Learn about America’s Red Rock Wilderness Act

Latino querencia for our public lands can bring the permanent protection of America’s redrock wilderness.

Will you join Latinos for Utah wilderness?

Listen to our Utah Silvestre Podcast Series

Utah Silvestre is a 4-part miniseries from the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance’s Wild Utah podcast. Hosted by Amy Dominguez and Olivia Juarez, each episode is available in both español and English, created for our gente to recognize that redrock wilderness is embedded in our community wellness, cultural histories, traditions, and our futures. We are breaking down barriers that America’s Hispanic and Latino/a/x community members encounter when they are concerned about the climate crisis and the state of nature.

Herencia y Querencia (inheritance, heritage, and care)

There is no term for “wilderness” in Spanish, nor in some indigenous languages of Latin America, to convey the concept of public lands, held in trust for all of America, in their natural state. Millions of acres of canyon, mesa, valley, river, grassland, forest, and mountain are the shared inheritance of every person in the United States, no matter where you come from. Every member of the American public is allowed to determine the future of Utah’s wild lands regardless of origin or documentation status. Whether or not you are a citizen, or you live anywhere from California to Puerto Rico, public lands are your herencia—by law and by culture.

Public lands of the Colorado Plateau have a unique significance to Latino, Chicano, and Hispanic cultures. Just as wild Utah is the ancestral homeland for indigenous peoples and Tribes in the southwest, these lands also are part of the past, present, and futures of Latinx communities today.

Latinos and Public Land Protection

Eighty-seven percent of western Latinos1 support a national goal of protecting 30% of America’s lands and waters in their natural state by the year 2030. By protecting nature, our public lands provide a solution to the climate crisis and even extinction of life across the world. Studies say that a football field worth of nature is demolished every 30 seconds in the U.S. This loss of nature—accelerated by climate change—is a threat to our community’s health and prosperity. It affects clean air, water, and defenses against severe weather, floods and wildfires across America. In the United States, only 12% of land is currently protected in its natural state. America’s red rock wilderness throughout Utah accounts for one-and-a-half percent of the remaining land that needs to be conserved to reach the goal of protecting 30% of land in the United States by 2030.

By protecting the deserts and mountains of Utah, our country also validates the values that Latinos have for public land. 77% of Latinos think that we should maximize land for conservation and recreation rather than energy development, and 81% of Latinos support making public lands a net-zero source of carbon pollution.2 When wild lands in Utah are conserved as wilderness, they validate these opinions because they keep carbon in the ground, and allow the land to absorb and store carbon that the atmosphere, in the ground and as plant matter.

With Latino grassroots advocacy for America’s Red Rock Wilderness Act, Congress can pass a bill that offers a solution to America’s wellness in times of climate crisis and loss of biodiversity.

1 2022 Conservation in the West Poll. Colorado College.

2 2021 Conservation in the West Poll. Colorado College

A Cultural Legacy

Historia

Latinos have deep roots and connection to America’s red rock wilderness. We deserve to have our stories told and reflected in the story of America. When we protect wild Utah, we protect Latino culture.

When Utah was México

Until 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the redrock, the mountains, and the forests that characterize the state of Utah were a part of México. Looking at a sandstone canyon is like looking into a time machine on a geologic and human scale. In the layers of rock and color, we see more than the emblematic nature of Utah, we also see Latino history. We see what the communities in the region saw when México gained independence from Spain. And still, that is late on the timeline of cultural history in the Colorado Plateau. For time immemorial countless tribes, pueblos, and bands of indigenous peoples recognized canyon country as their patria. Even the peoples whose descendants would eventually become known to the world as Latinos, Latinas, Latinx or Hispanic.

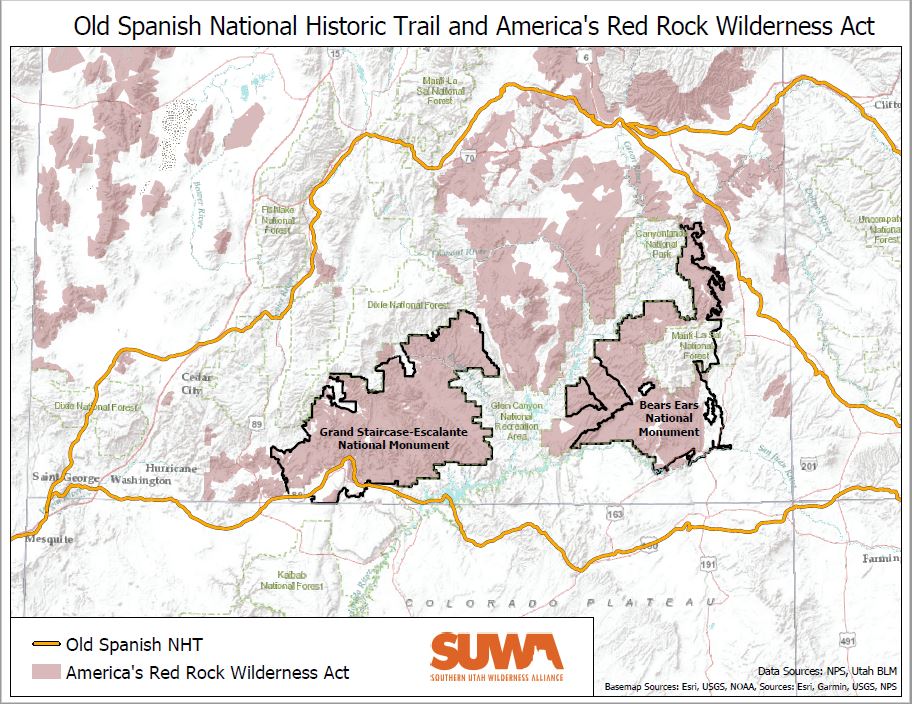

The Spanish Trail

Historically, Hispanics and others became acquainted with America’s red rock wilderness through using the old Spanish Trail. Places like the Antelope Range near Cedar City, Joshua Tree habitat near St. George, and the expanse of redrock country through Grand County and Emery County, Utah are directly adjacent to the Old Spanish trail. In fact, the trail runs directly through the southwestern span of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. When looking upon America’s red rock wilderness we get a glimpse into the state of the country even long before the trail was established in 1829.

Place names

Latino and Hispanic culture is even in the names given to regions of America’s red rock wilderness. Places like the San Rafael Swell, Virgin River, Mexico Point, Mexican Mountain, San Juan River, the Green River (called the Río Verde by Spaniards), and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument are names given by Spanish and Mexican nationals, or are names given in honor of them. Of course, these places like anywhere else in America’s redrock wilderness have names in the different languages of tribes in the region. But as the map reads now, Hispanic and Latino cultural influence is written onto public land. It’s also painted onto the redrock.

Mesoamerican Relationships

Historical objects studied by archaeologists also characterize Latino heritage of redrock wilderness. Feathers from scarlet macaws and military macaws, which inhabit the gulf coast of México, Central America and South America, have been identified at Bears Ears National Monument and near Canyonlands National Park. The feathers were used by Ancestral Puebloan people. How did these bright plumes get to canyon country? Trade between Mesoamerica and the Colorado Plateau played an important role. After dating of macaw remains in 2015, scientists agree that macaws were acquired persistently from Mesoamerica between A.D. 900 and 1150.

In the nearby Chaco Culture National Historic Park, cacao and ceramic drinking vessels have been recovered from Pueblo Bonito, suggesting that Ancestral Puebloans also consumed cacao drinks. Like macaws, cacao originates in the tropics of Central America, South America, and parts of México.

What does this all suggest? That the indigenous peoples of the southwest had relationships with Mesoamericans: the ancestors of many current day Mexicans, Central Americans, and South Americans. Latino ancestors were part of the same historic world as Ancestral Puebloans–a world which we can know of because Utah wild lands have remained in their natural state. Mesoamericans and people on the Colorado Plateau articulated with each other, influencing Ancestral Puebloan life in redrock country. Conservation of America’s red rock wilderness is also a Latino historical preservation of the astonishing feats of pre-Hispanic long-distance travel and cultural exchange.

Utah wilderness remains crucial for archeologists to learn more about the relationship between Mesoamerica and the Colorado Plateau. As a nation, we do not yet know everything there is to know about American history from redrock wilderness. Any loss of America’s redrock wilderness is a deficit to science and cultural preservation, which may include ancestral Latino cultural preservation.

Latino and Hispanic history and culture in Utah runs as deep as canyon and mesa walls. These stories can still be remembered and celebrated thanks to the fact that Utah wilderness through human history has been changed by nothing more than wind, water, and sun. In this vein public land is truly nuestra herencia. It cultural heritage as well as inheritance, which is a precious gift worth guarding. Show your querencia (care and affection) for Utah wilderness by taking action now.