President Trump’s repeal of Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments on December 4, 2017 represents the single greatest attack a president has ever launched against America’s federal public lands. With the stroke of a pen, Grand Staircase was slashed by 47 percent, with about 1 million acres remaining, and Bears Ears was decimated, its 1.35 million acres reduced by 83 percent to just 229,000 acres.

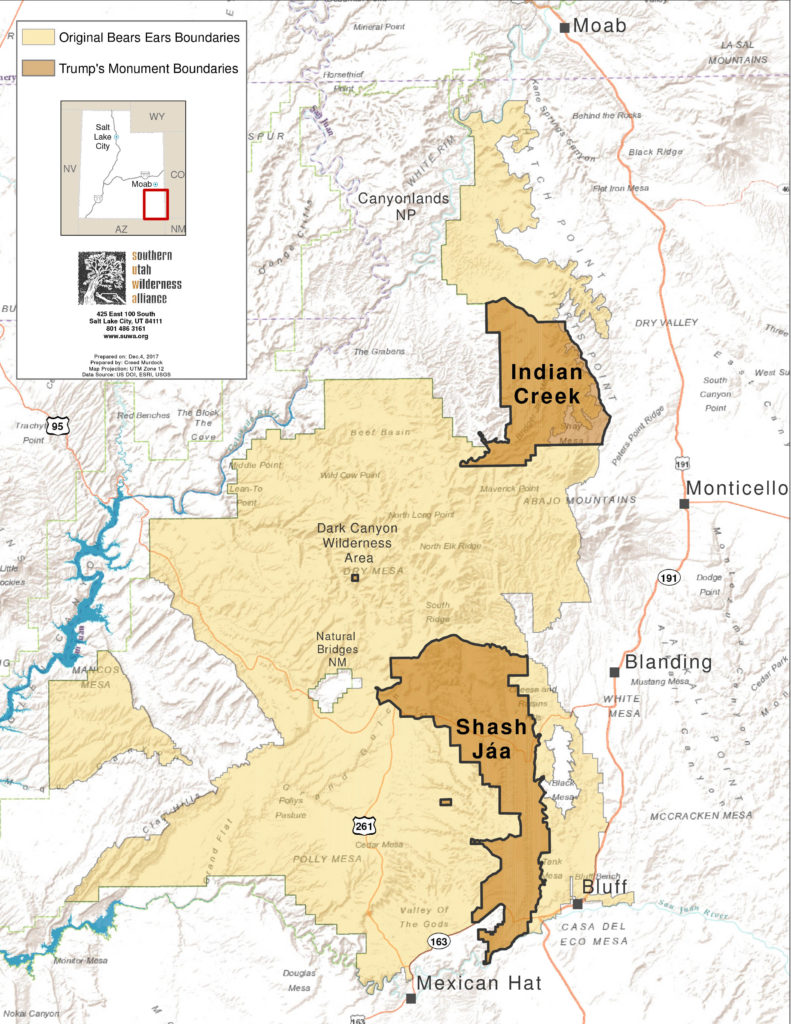

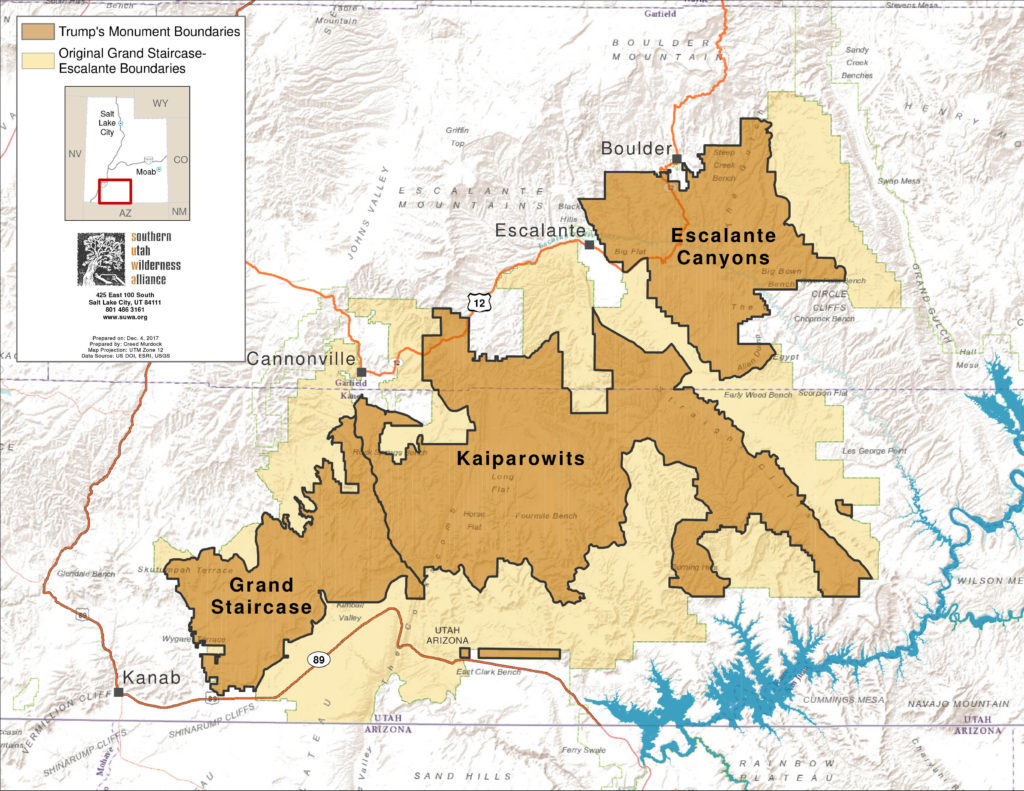

This unprecedented and illegal action revokes needed protections from world-class scenic and historic landscapes. The maps below show just how dramatic the changes are (click images to enlarge).

Bears Ears National Monument |

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument |

But more than merely lines on a map, the original boundaries of Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears National Monuments were deliberately drawn to protect these areas’ remarkable natural and cultural resources. Trump’s evisceration of these national treasures puts the following places, among many others, under threat of development and abuse.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

By eliminating nearly half of Grand Staircase-Escalante, President Trump has opened up some of the most wild and scenic redrock canyons in Utah to the lost cause of coal mining. For 21 years, this monument has inspired families to reconnect with the wild and with each other, has reinvigorated surrounding communities, and has lead to significant paleontological discoveries. It has even been affirmed and ratified by Congress. Trump’s grandstanding disregards the success of this monument, merely because Utah’s Senator Hatch instructed him to.

Kaiparowits Plateau

Running much of the southern border of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, the Kaiparowits Plateau is one of the most remote and least visited wilderness landscapes in the southwestern United States. The sheer size, rugged topography, and isolated nature of the Kaiparowits Plateau make it a refuge for a remarkable variety of plants and animals. In addition, the region contains a wealth of paleontological treasures, with the vast majority yet to be discovered. Unfortunately, Utah politicians have long held a fool’s dream of developing a large-scale coal mine in this remarkable area. With monument protections removed, the Kaiparowits Plateau once again becomes ground zero for future coal leasing and development—a devastating blow to the landscape’s natural and paleontological resources.

Cockscomb

The Cockscomb, a prominent serrated ridge running north to south through the heart of Grand-Staircase Escalante National Monument, is a scenic and geologic wonder. The Cockscomb’s winding sandstone cliffs and canyons offer limitless exploration, while the Paria River, running along the southern portion of the escarpment, provides important riparian habitat. Irresponsible motorized recreation will become a greater threat with the removal of monument protections.

Circle Cliffs

The Circle Cliffs, a geologic amphitheater in the northeastern portion of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, is a unique and remote landscape. The towering sandstone Circle Cliffs, previously eyed for tar sands development, are once again threatened by dirty energy and the location and development of uranium mining claims.

Hole-in-the-Rock

The historic Hole-in-the-Rock corridor runs from the town of Escalante to its terminus at the Colorado River, and provides ready access to many of the world-famous canyons of the Escalante River. Kane and Garfield Counties—two of Utah’s most rabid anti-environmental voices—have long sought to pave the entire length of the Hole-in-the-Rock Road to promote large vehicle travel. In addition, paving the road would help facilitate a plan to develop a Utah State Park near the end of the 62-mile road. Conservationists have long opposed these developments as they threaten the remote and wild character of this portion of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

Bears Ears National Monument

The effort to protect Bears Ears as a national monument was led by a historic consortium of sovereign tribal nations: the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, and Ute Indian Tribes. For the first time in American history, these Tribes would have a greater say in the management of these culturally important lands. In addition to protecting some of the most spectacular landscapes in southern Utah, the original Bears Ears proclamation covered 100,000 archaeological and cultural sites, including House on Fire and Moon House ruins. President Trump’s decimation of Bears Ears by an outrageous 83 percent is just the latest in a long string of insults he has lobbed toward Native Americans.

White Canyon

Located in the western portion of Bears Ears National Monument and bordering Natural Bridges National Monument, the upper drainages of White Canyon are the places that backcountry dreams are made of. The canyon walls are honeycombed with alcoves, arches, windows, hanging gardens, and grottoes; the canyon floors are riddled with potholes. The White Canyon complex, which includes over a hundred miles of narrow and sinuous canyons, not only provides abundant canyoneering opportunities, but also contains innumerable cultural resources and thousands of acres of important desert bighorn habitat. This pristine natural and cultural landscape is now threatened by new uranium mining exploration and development.

Lockhart Basin

Located near the eastern rim of the Canyonlands Basin, Lockhart Basin forms a contiguous landscape with the northeastern boundary of Canyonlands National Park. In fact, Lockhart Basin was omitted from the final park boundary due to political compromise rather than worthiness. Geographically, geologically, and aesthetically, Lockhart Basin is an integral part of the Canyonlands Basin. Open to development and once the target of historical oil exploration, new technologies now put Lockhart Basin back on the list of areas threatened by future oil and gas leasing and development.

Cedar Mesa

With its abundance of significant cultural sites, Cedar Mesa is a living gallery of cultures past and present. Cliff dwellings made of mud and stone perch like swallow’s nests on south-facing canyon exposures, while scatterings of broken pottery, corncobs, and lithic scatters hint at the daily lives of the ancient ones. Circular kivas where the Ancestral Puebloans gathered underground for religious ceremonies are evidence of their spiritual legacy. The density of cultural sites within this region, up to several hundred sites per square mile, may be as great as any other place in the United States. These irreplaceable treasures are threatened by both looting and unintentional damage, which will continue without the monument’s emphasis on protecting cultural resources.

Grand Gulch

Cedar Mesa’s counterpart to the west, Grand Gulch contain hundreds of miles of serpentine canyons, a wealth of pristine archaeological sites, and crucial habitat for sensitive plant species as well as wildlife such as mule deer and desert bighorn. The cultural resources of this area are threatened by both looting and unintentional damage, both aggravated by irresponsible motorized vehicle use. These problems will continue without the monument’s emphasis on protecting cultural resources.

Beef Basin

Most well known for Ruin Park, an open expanse of grasslands containing unique and significant archaeological sites, Beef Basin is a wild landscape bordering the eastern boundary of Canyonlands National Park. Tower ruins, cliff dwellings, and lithic scatters abound in this wild and remote region. The cultural resources of this area are threatened by both looting and unintentional damage, which will continue without the monument’s emphasis on protecting cultural resources. This area is also a focal point for additional pinyon and juniper clear-cutting projects.

Valley of the Gods

Tucked below the high plateau of Cedar Mesa, the aptly named Valley of the Gods is an awe-inspiring expanse of isolated monoliths and sandstone spires. Located in the southern portion of Bears Ears National Monument, the valley’s pinnacles, escarpments, and cliffs dwarf visitors while hidden canyons provide endless exploration and shady respite. Irresponsible motorized recreation continues to impact this unique and sensitive landscape, and the area has been targeted for developed tourism infrastructure.