Reports From the Field is a blog of SUWA’s Field Volunteers, accounting experiences, reflections and activism from time spent in direct service of Utah’s wild and public lands.

When hiking and exploring Bears Ears National Monument, it is easy to lose oneself in the beauty and isolation of its many canyons. The serene beauty found in the region now widely associated with the Bears’ Ears buttes is one of the main appeals of this landscape. However, a scan of the canyon walls and alcoves reveals glimpses into the distinctive and vibrant cultural history of the region. While many call Bears Ears a wilderness, it was called home by generations of indigenous peoples, whose artwork, architecture, and objects of daily life may still be found throughout the Bears Ears cultural landscape. As an archaeologist, I can attest to the scientific significance of these sites, but more importantly these are places of cultural identity and spiritual importance to descendant Native American communities.

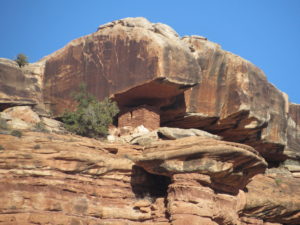

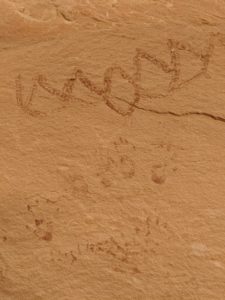

I had the chance earlier this month to explore one such cultural space with a backcountry cleanup project organized by SUWA at Fish and Owl Canyon. Our crew of volunteer scientists and professionals performed trail maintenance, cleaned out and dispersed illegal fire pit rings, and carried out trash left by hikers. All the while, we were witness to archaeological sites throughout the canyons. A granary tucked beneath a rock overhang. A scatter of ceramic sherds on a talus slope. A stark white pictograph above a habitation site.

These were all created by the Ancestral Pueblo culture over 700 years ago, amid a time of social unrest and environmental uncertainty. The placement of dwellings in nearly inaccessible canyon alcoves has been interpreted by many archaeologists as an indicator that defense and security were a priority for the people who called these canyons home. Our small contingent approached one such site, but were appropriately foiled by the steepness of the surrounding slickrock. Even amid a time of uncertainty, the people who dwelt in Fish and Owl Canyons still filled their lives with beauty, craftsmanship, and sustenance, as seen in pictographs adorning the canyon walls, black-on-white ceramic sherds found beneath a site, and corn cobs lying on a dry alcove floor.

I first hiked Owl Canyon in 2009 and remembered well the ruins, rock art, and artifacts found throughout the canyon. On this return trip I was happy to see that the ruins and rock art appeared undamaged and still in good condition. However, I was disturbed to find the wealth of ceramic sherds that once adorned sites were largely gone. In less than a decade, a deluge of visitors had carried away these pieces of the Bears Ears cultural landscape. As we all continue to fight for the legal protection of Bears Ears, it is just as important to continue to educate a public unfamiliar with the proper etiquette required to visit cultural sites. Our cleanup work helped reverse recent human impact on the canyon environment, but a respect for the cultural legacies of Bears Ears is essential for the continued preservation of this landscape.

Maxwell Forton, Archaeologist

Binghamton University