Three years ago Rep. Rob Bishop (R-UT) announced that he would boldly go where few had dared before: to broker legislation for the public lands of eastern Utah. Early on dubbed the “Grand Bargain,” Bishop intended this to resolve longstanding public lands disagreements.

Much of that early promise has faded as it becomes increasingly apparent that Utah’s rural county commissioners—a numerical flyspeck in a nation of 325 million people—are being handed the keys to the fate of our national public lands. No longer worthy of the name “bargain,” either grand or petite, this effort has become known as the “Public Lands Initiative” (PLI).

While the PLI legislation has not been released, it is clear where it is headed. Rep. Bishop’s partner in this effort, Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-UT), recently said it was no secret that the PLI legislation would largely be what the county commissioners proposed. If so, the prospects for real conservation are grim.

A Monument Looms

It is worth recounting how we got to this point. What drove Bishop to seek a Grand Bargain? In short, the possibility of a new national monument in Utah.

The 1906 Antiquities Act gives the President authority to protect public lands as national monuments. Arches, Capitol Reef, Bryce Canyon, and Zion national parks were first protected that way. That same authority created the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

When the Grand Bargain process began, several Utah national monument proposals were circulating. The delegation openly worried that unless it acted, the President would use his authority to protect public lands. Utah political leaders have long insisted they could develop a workable formula for the management and protection of Utah’s remarkable public lands. The threat of new monuments focused their minds on precisely that task, one they knew would demand meaningful conservation.

A New Beginning

The conservation community lauded Bishop’s willingness to undertake the difficult task, and Bishop announced that his effort would be different from previous ones. Early on, it certainly seemed so. There was a palpable change of tone in meetings between traditional antagonists. Most approached this effort with open minds and listening ears. To demonstrate our goodwill and good faith, conservationists offered early concessions.

Daggett County: A Case Study

Daggett County: A Case Study

Soon, in Daggett County, it seemed we had struck gold.

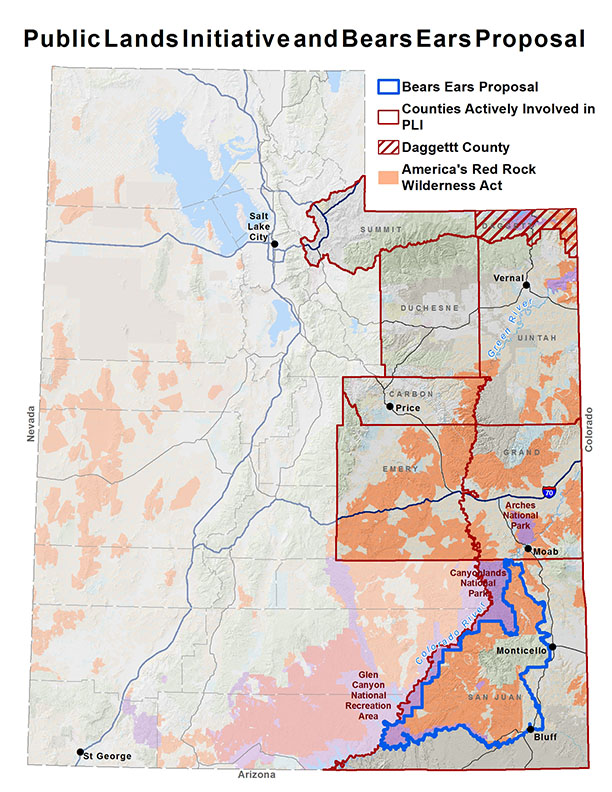

At the Utah Capitol in October 2014, we joined Bishop, Daggett County commissioners, Gov. Gary Herbert, our conservation partners, and staff members from Chaffetz’s and Sen. Mike Lee’s (R-UT) offices. We announced an agreement regarding the public lands of this small northeastern Utah county, the first under the Grand Bargain.

The details were exciting. The proposal would protect the lion’s share of lands in Daggett County proposed for protection in America’s Red Rock Wilderness Act. It also included a novel exchange of BLM lands and Utah school trust lands that we hoped would create a powerful precedent. Rep. Bishop said he would include the agreement in his Grand Bargain legislation. He hailed this arrangement as a model for the rest of the counties to follow, a view many shared. The Deseret News called it a “home run.”

Unfortunately, Daggett County soon became the exemplar of what is wrong with this effort today: one single Utah county commissioner has final say on lands belonging to 325 million Americans.

When the Daggett agreement was struck, two of the three county commissioners were leaving office at the end of the year. One of the incoming commissioners, who ran unopposed, soon declared his opposition to the agreement. He rabble-roused, complained, and attacked it—in essence, because it included any conservation at all. Bishop capitulated and said he would no longer honor the Daggett agreement.

In Daggett County leadership, compromise and reason fell to the animus of one county commissioner representing just over 400 voters. And the Grand Bargain faded away, to be replaced by the PLI.

In the PLI, Bishop and Chaffetz no longer aspired to a comprehensive resolution of the public land wars of eastern Utah. They handed over the process to rural counties, none of which would be called upon to make serious compromises.

Counties Run Wild

In some counties—Grand, Uintah, and Duchesne—commissioners were willing to talk to groups like SUWA. Other counties refused even cursory discussions. San Juan County specifically said it would not take input from anyone outside the county in developing its public lands proposal. It would not even listen to Indian tribes, such as the Hopi or non-Utah Navajos, despite their direct cultural and ancestral ties to these lands.

It would be one thing if San Juan County’s proposal were meant to be a starting point for discussion. It isn’t. Chaffetz recently said publicly that he considered the PLI process for San Juan County to be over. He explained that anyone was welcome to travel to Monticello for county meetings (never mind the fact that the county said it would not listen). But there would be no input sought from anyone else.

Common sense shows that this is a sure recipe for failure; history concurs. This is the same approach Utah’s congressional delegation embraced in 1995 for its ill-fated statewide wilderness proposal: put county commissioners in charge and ignore the views of everyone else.

County commissioners have little incentive for compromise and are easy prey to parochial interests. The icons we celebrate are diagnostic of an ethos. For example, The Utah Association of Counties just named Phil Lyman its 2015 county commissioner of the year. Commissioner Lyman (of San Juan County) was convicted earlier this year for leading an illegal off-road vehicle ride into Recapture Canyon—an area closed to vehicles to protect its wealth of cultural artifacts.

In the PLI, this is who runs the show.

An Un-Wilderness Bill

What does a rural-Utah-county-produced PLI look like? It is a grab bag of gifts for counties. County-conceived legislation is likely to designate thousands of miles of RS 2477 rights-of-way while still allowing counties to litigate claims inside designated wilderness. RS 2477 is a Civil War-era statute that encouraged settlement by granting rights-of-way across public lands; in Utah it has served as a tool to block wilderness by insisting that footpaths and wash bottoms are actually highways.

One county official enthusiastically described how the PLI will use alleged RS 2477 rights-of-way to create “un-wilderness” areas. A threshold feature of wilderness is roadlessness. If the PLI creates a spiderweb of legitimized routes across our public lands, those areas will be roaded, not roadless, and thus forever disqualified from wilderness protection.

The parade of horribles continues. If the counties prevail there will be land giveaways and a land exchange tilted heavily in the state’s favor. In areas designated for conservation, it’s possible the legislation will create more safeguards for grazing than exist on uprotected public lands. Vast areas will be designated energy zones with energy development given top priority. In fact, the counties propose more acreage for energy zones than for conservation.

The cherry on top of the bill is a permanent restriction on the President’s use of the Antiquities Act authority in the PLI counties.

“Benefits . . . ?”

As for the “benefits,” Chaffetz said that the PLI will include roughly 3.9 million acres of protection. In other words, if we’re lucky, the PLI may end up “protecting” almost as much land as is already managed for protection. For example, about 10 percent of this acreage comes from wilderness designated inside of already-protected national parks.

Nearly half the total comes in the form of ambiguous National Conservation Areas or other novel designations. Every county has proposed different management guidelines for these areas; many would actually weaken land management compared to current BLM practices.

Another 40 percent of the 3.9 million acres would be designated wilderness outside parks—more sleight of hand. This acreage total is less than what the BLM today manages as wilderness study areas and natural areas (two different forms of administrative de facto wilderness) in the PLI counties.

In summary, we have a one-sided deal: under the PLI, areas that are already managed for protection will be permanently designated—subject to continuing litigation from the counties. In exchange, we’re asked to swallow major weakening of management guidelines for those protected areas, giveaways to counties, carbon-generating energy zones, and no more Antiquities Act authority.

We Continue to Hope

At press time, the Utah delegation is drafting its legislation. We hope it will be more than just a county-produced PLI. We hope the delegation will seek conservation, compromise, and public involvement as it proceeds. We are ready to be part of further discussions and negotiations to craft a wilderness bill that will serve posterity and this spectacular landscape. The PLI’s current trajectory, however, makes daring to hope seem like wishful thinking.

History shows what the likely fate of a county-driven wilderness process in Utah will be: failure. If that is the case, we should not be surprised that the very thing that started this process—a national monument—is also the thing that ends it.

—David Garbett

(From Redrock Wilderness newsletter, autumn/winter 2015 issue)