Campaigns to steal America’s western public lands are not new. Every few decades they sneak out of the shadows to pester the fair minded and attempt to swindle our national heritage.

Opponents of public lands—led by the likes of Cliven Bundy, Phil Lyman, and Ken Ivory—are now back at it, hoping to prove that, if nothing else, history repeats itself. They argue that our vast national heritage of public land is an affront to the Constitution. They claim that states are the rightful and proper owners.

These claims are spurious and ultimately just a smokescreen for the true root of this movement. What Bundy, Lyman, and Ivory are really seeking is power.

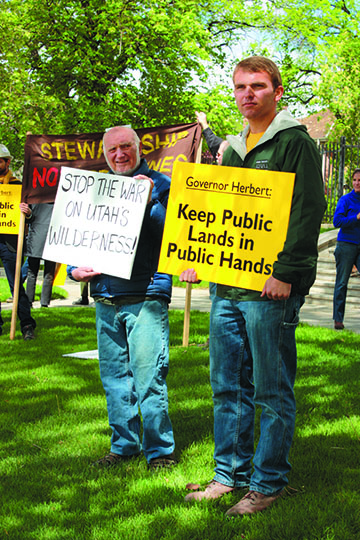

Our public lands are too remarkable of a treasure to be lost to the ambitions and selfishness of a few. As previous efforts to steal our national heritage have failed, let us ensure that this current attempt meets the same fate.

Wrong on History

The first thing that the land grabbers have wrong is history. Ivory may be the major offender. He is the Utah legislator who sponsored the state’s land grab legislation a few years back and is now its biggest crusader. Ivory conveniently cherry-picks self-serving quotes and random tidbits of history in spinning his tales, carefully ignoring the actual events surrounding statehood grants to the public lands states of the West. Utah, typical of these states, joined the nation with the understanding that it was giving up any claim to the public lands within its borders. This understanding is permanently memorialized in its state constitution.

Lest there be any confusion, one year after Utah became a state its first national forest was set aside. Known as a “forest reserve” at the time, it was a tract of land reserved from the standard disposal laws (i.e., laws intended to dispose of federal lands). In other words, the federal government made clear it did not intend to relinquish those lands. Utahns of that day reacted differently from Ivory and his acolytes: rather than decry some sort of federal tyranny, Utahns asked for more.

One such request came from the Priesthood Session of the 1902 Mormon General Conference (a twice-yearly gathering in Salt Lake City of all Mormons). There, the Mormons voted in favor of asking the federal government to set aside more of Utah’s forests.

Those early Utahns saw the wisdom of managed public resources. On the question of whether Utahns thought statehood meant that all federal land was to be given up, whom shall we believe: Ken Ivory as he twists the facts over a century later, or Utah’s largest interest group speaking within six years of statehood?

Wrong on Economics, Too

A review of the economics does not help the land grabbers either. The Utah Legislature commissioned a study to see if the land grab could pencil out financially. The study showed that it was unlikely Utah could afford the land. Under most scenarios, the state would lose millions each year in taking over federal lands. Only if oil and gas prices were to climb well above their current levels and stay there would the state be able to cover the costs.

When Utah passed the Transfer of Public Lands Act in 2012 demanding the end of federal land ownership, it cited economics. The land grabbers declared that Utah needed to do this to fund its schools. But they had never actually run the numbers. So when they got around to an analysis that produced dire prospects, did they quickly abandon their demands for the “return of our land”? Of course not.

This has never been about the economics of the general public welfare. Ensuring the financial health of a handful is as close to economics as land-grab thinking gets. Now that actual research shows that the math of the land grab stinks, crusaders have retreated to anecdote and make-believe to tout their scheme (see sidebar, right).

Failing the Legal Test

Most significantly, Ivory and his crowd are wrong on the law. Nearly everyone with a law degree that has evaluated the legal arguments of the land grabbers finds them to be complete bunk. The two exceptions to this are the lawyers whose paychecks depend on agreeing with the land grabbers—the Utah Attorney General, for example—and apparently one law professor. While the Utah Attorney General says the state has a case, he is not running to the courts with it. He quietly let the state’s ultimatum that the federal government give public lands to the state before 2015 pass without any action. One law professor concludes that the land grab arguments are “serious” because they are based on a historic promise, but he relies on a tortured interpretation of history rather than dealing with the actual events of statehood.

Phony Land Management and Fires

Finally, the land grabbers have their land management policy wrong. Ken Ivory’s favorite way to start an anti-public land sermon is with the tragedy of forest fires. To believe him is to believe our forests are all burning because of federal land mismanagement today.

Ivory never mentions the wrongheaded history of western fire suppression: that we have frantically doused every spark for a century and more. There is no reference, either, in Ivory’s catechism, of a warming planet or of stubborn drought and their effect on forest fires.

Neither does Ivory ever propose what you might call an actual solution to forest fires. Instead, a tautology suffices: the lands must be turned over to the states because that is the only solution. But what will the states do differently? As he never really answers this question our best guess is that he thinks if we eliminate forests, we eliminate forest fires. It would be logging on steroids and Red Bull. In Ivory’s world, no natural system should ever be allowed to operate naturally. A vibrant, healthy, standing forest—that, yes, even includes dead trees—is an affront to someone who believes the destiny of every tree is to fall to the chainsaw.

Ironically, the issue of forest fires, while serving as their favorite policy argument, is also the land grabbers’ biggest policy hurdle. Fighting forest fires is spectacularly expensive. Indeed, the potential bill is so astronomically high that it is probably the first reason why many states have not stocked up on Ivory’s magic elixir.

“Trust Me”

Ivory declares that states will manage the lands better than the federal government because they are closer to the resources. That is also a description of parochialism—precisely the sort of parochialism that led to the creation of federal land management systems in the first place. No entity short of the federal government will manage for the broad national public interest against those “closer to home” power blocs that dominate lower levels of government.

History gives a clear picture of how Utah would manage public lands if ever it should lay hands on them. At statehood, the U.S. granted Utah one-ninth of its land base as state lands. Over half of that endowment has since been sold. Not too long ago, the Utah Supreme Court made clear that state lands below the beds of navigable waters were open to public access. The Utah Legislature has subsequently done everything it could to undo that ruling by whittling away public access as a sop to landowners. And Utah’s state parks continue to be severely under-funded. Just a few years ago the legislature considered closing some to cut costs.

Seeking Power

This movement has always been about power and control. The efforts of Cliven Bundy and Phil Lyman illustrate this clearly.

Bundy needs little introduction. More than twenty years ago he began refusing to pay fees for grazing his livestock on public lands. He defied court orders and even an attempt to confiscate his cattle, with the help of an armed gaggle. Bundy does not recognize federal lands and he does not recognize federal authority. In short order it became apparent that Bundy was a racist after making insensitive remarks about African Americans. His racism seemed symptomatic of an inability to empathize with the plight of others or think outside himself.

Another such darling of fed-haters is Phil Lyman, the San Juan County, Utah, commissioner who led an illegal ATV ride into Recapture Canyon—an area closed to vehicles due to its abundance of cultural resources (see sidebar, opposite page). A movement’s heroes tell us much about its principles.

So what lofty ideals do these two land grab proponents represent? Taking public resources without paying for them. The “right” to drive an off-road vehicle anywhere one pleases, including over sacred cultural sites. This is what passes for high principle among the land grabbers: theft of the public estate.

Contrast these two with the writers and thinkers that have advocated throughout the years for public lands. These are heroes of conservation like John Muir, Aldo Leopold, Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, Bernard DeVoto, and Terry Tempest Williams. They have all written compellingly about the value of wild places and open spaces, of their ability to inspire us, to heal us, and to reform us.

But even the land grabbers will eventually lose out with their ephemeral dream of ending federal management. Ironically, the inevitable privatization of land under their scheme will ultimately deprive even them of the control and power they seek.

Meanwhile, they will have deprived the rest of us of a treasure. They must not be allowed to win and we will not let them. For our sake, and that of posterity, as well as the plants and animals that depend upon these landscapes, we must keep our public lands.

—David Garbett

(From Redrock Wilderness newsletter, summer 2015 issue)