Gambling with Public Lands:

The BLM’s Risky Vegetation Removal Program and its Impact on Wildlife, Climate, and 30×30

Vegetation removal projects take many forms. At the most basic level, the BLM uses:

- Chainsaws to topple pinyon pine and juniper trees before scattering sawed-up pieces around the site.

- Herbicides to kill sagebrush and pinyon and juniper saplings.

- Prescribed fire to remove tree saplings and shrubs

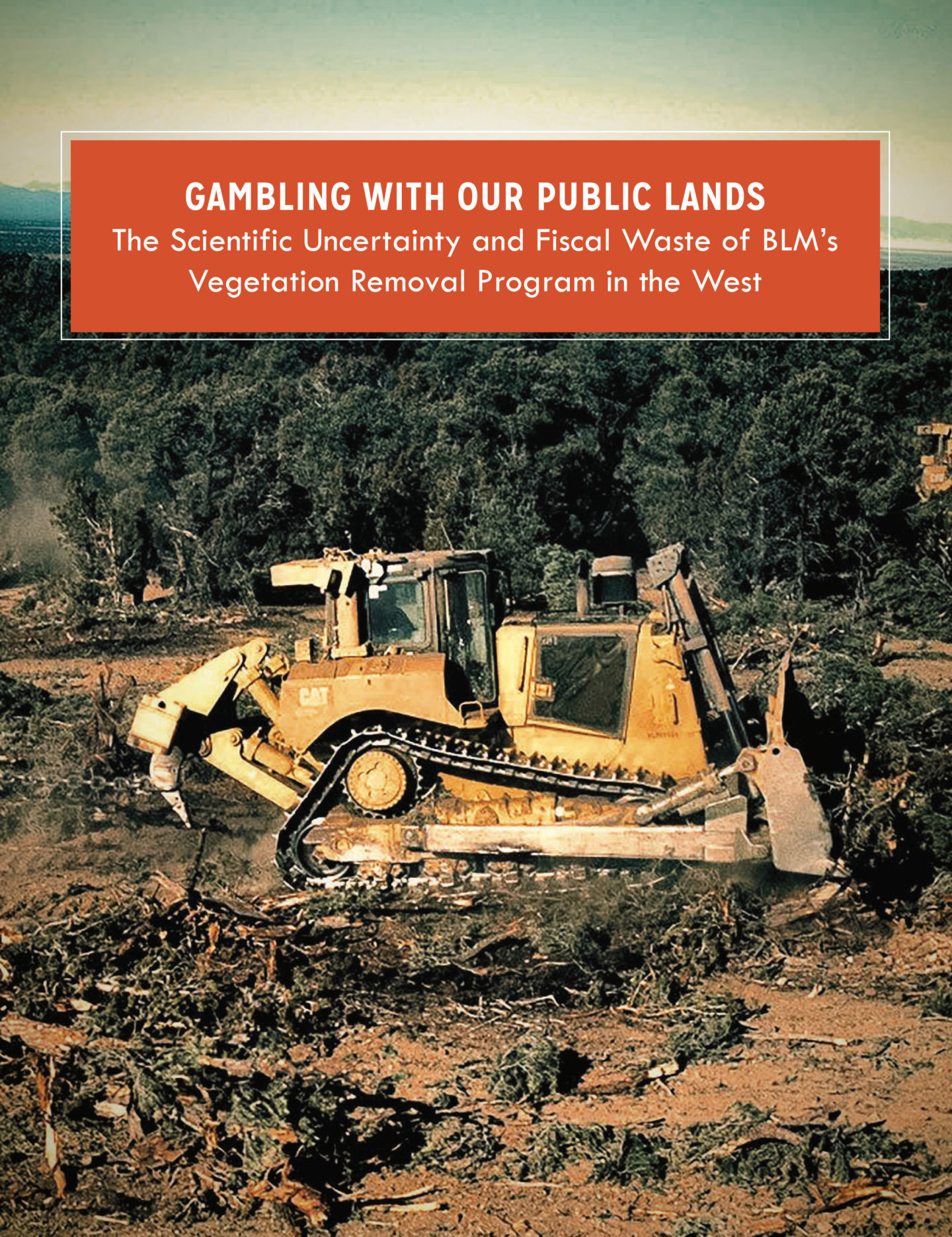

More commonly, the BLM resorts to intensive mechanical methods, employing heavy machinery to accomplish similar ends:

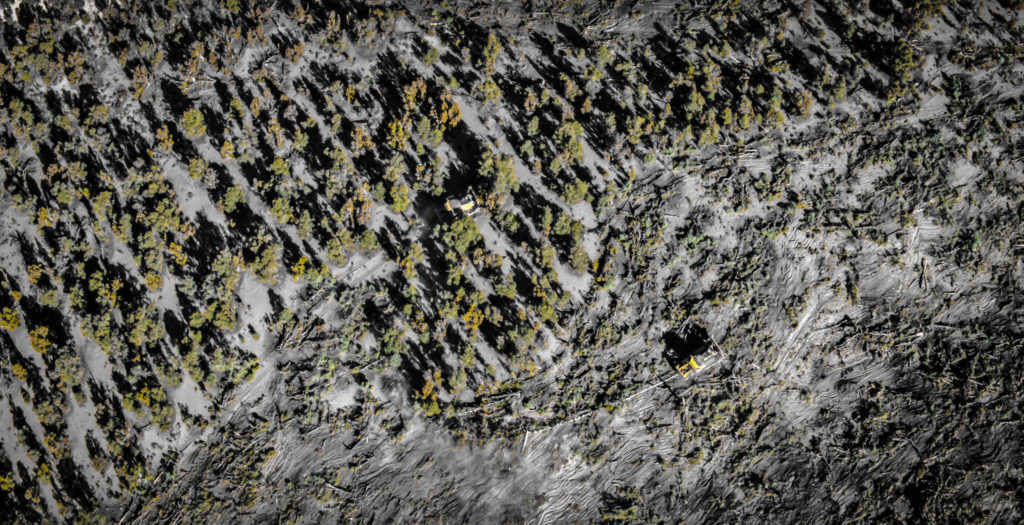

- Bull Hog Masticators mow down trees with giant mulchers attached to front-end loaders or excavators. These machines turn living trees into piles of wood chips and stumps, quickly removing whole stands of native pinyon pine and juniper.

- The Dixie Harrow Method uses a tractor to drag a 25- to 50-foot-wide frame with large teeth welded to parallel bars, churning soil and uprooting vegetation.

- Chaining uses a large anchor chain, which can weigh more than 20,000 pounds, dragged between two enormous bulldozers to tear trees out of the ground, roots and all, flattening hundreds of trees with every pass. As the chains rake across the surface, soils, sagebrush, grasses, and forbs are destroyed. The discarded trees left in their wake can litter the landscape for decades.

A 2019 report released by Wild Utah Project – a Utah-based non-profit organization focused on conservation science – analyzed the existing scientific literature on mechanical vegetation removal projects in western pinyon-juniper and sagebrush communities to determine the state of current science and identify gaps in understanding regarding these potentially harmful projects.

The scientific analysis raises important questions as to why the BLM is gambling taxpayer money to destroy native landscapes on our public lands. Below we outline the major concerns.

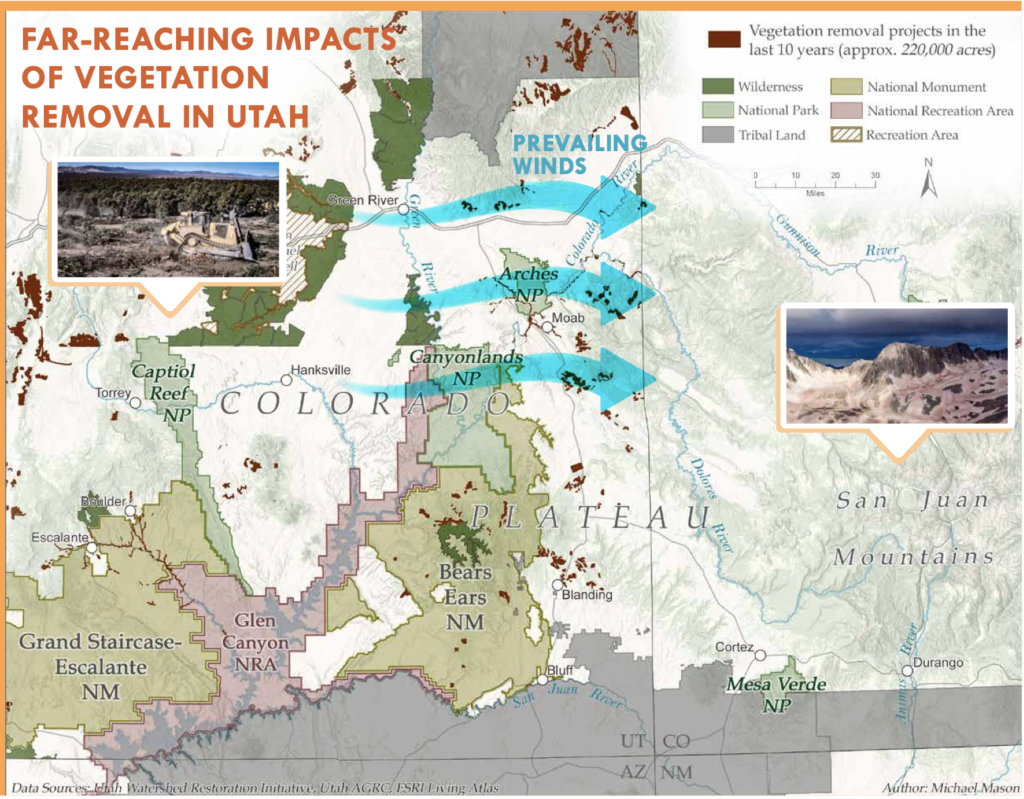

Red Dust on White Snow

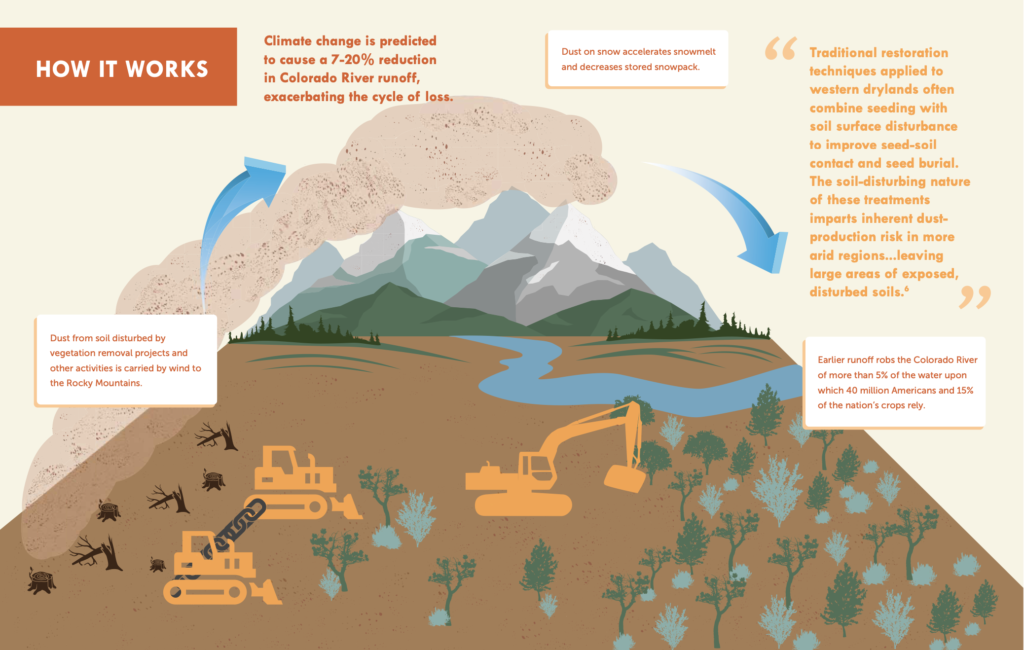

Here’s how it works: Wind storms pick up desert soils from the Colorado Plateau that have been disturbed by activities such as vegetation removal and grazing. Those wind storms then deposit that dust on mountain snowpack throughout the Rockies.

Today, dust is being deposited at rates approximately five times those of the era predating European settlement as a result of vegetation removal, grazing, off-road vehicle use, and resource extraction. When that dust lands on snow, it causes enhanced absorption of solar radiation—just like wearing a dark t-shirt outside on a hot, sunny day.

That enhanced solar radiation causes snow to melt faster and sooner than it normally would. Studies of the moderately dusty years of 2005-08 show that dusty snowpack reduced the Colorado River’s flow by about five percent (750,000 acre-feet)—or about double what the city of Denver uses each year.

This deposition of dust on snow appears to be increasing. During 2009, 2010, and 2013, scientists observed unprecedented amounts of desert dust falling on Colorado snowpack, about five times more than observed from 2005 to 2008.7 Various models predict that climate change will cause an additional 7-20 percent reduction in current runoff in the Colorado River Basin.

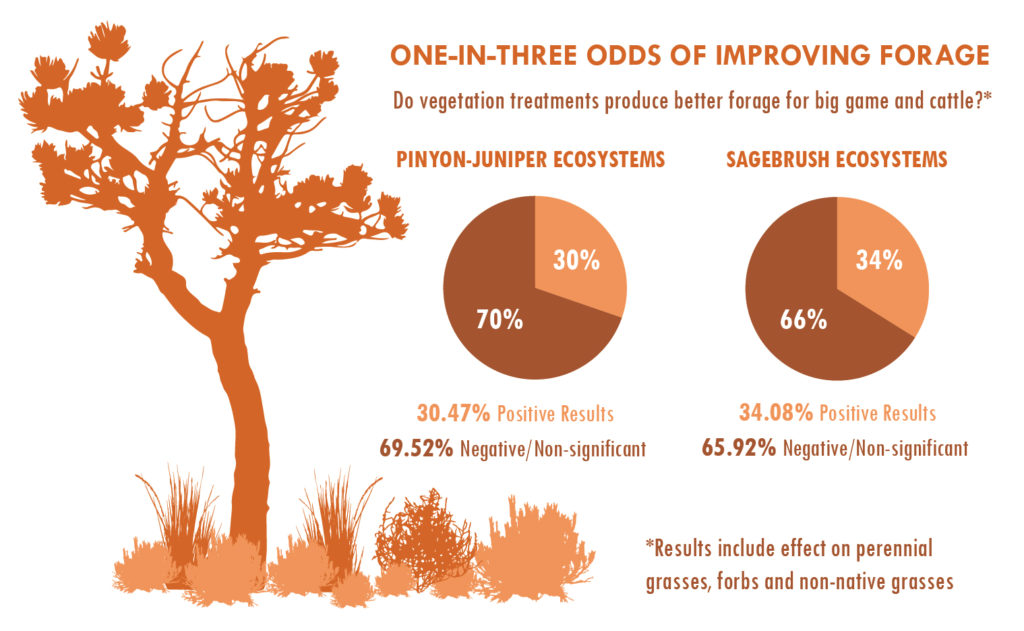

Bad Odds, Bad Returns

A Slippery Slope for Wildlife

While improvement of wildlife habitat is often a primary rationale for vegetation removal in both pinyon-juniper and sagebrush communities, existing science shows that the results of these projects are uncertain at best.

Half of the existing data points regarding the effect of vegetation removal on wildlife in sagebrush habitat show either a negative impact or “no significant effect.” For projects in pinyon-juniper woodlands, the report states that “the general trend across studies was for non-significant results of mechanical removal.”

One exception to the “non-significant results” trend was a negative impact to bird species that require pinyon-juniper habitat, such as the pinyon jay. The report notes that managing wildlife habitat is extremely complex and that “what benefits one species may be a detriment to another. . . . This argues against large expanses being treated with one method that creates a single homogenized vegetation community.”

Ignoring the Effects of Livestock

Ignoring the Effects of Livestock

According to the report, livestock grazing on public lands is “a widespread land use inextricably woven into vegetation dynamics throughout the West.” The report found that the majority of research into vegetation removal “does not control for [livestock grazing], either before or after treatment.”

While livestock are typically removed from the site during treatment and for 1-2 years afterwards, “few studies return and assess treatments on a longer-term basis when livestock have returned to the site.”

How can a land manager ever determine the proper vegetation removal method or the success or failure of a project if livestock grazing isn’t considered or analyzed? As the report states, “[f]ailing to account for the effects of livestock grazing makes it difficult to assess the causal factors of ecosystem condition and draw implications for management.”

No Fix for Fire

Vegetation removal projects are often proposed for the purpose of preventing large-scale wildland fires in pinyon-juniper woodlands, but the science doesn’t support this argument. According to the report, existing vegetative conditions are not always the driving cause of wildland fire and, in some instances, mechanized vegetation removal may result in increased invasive species that lead to increased fire danger.

“[R]ecent studies suggest that climate has a greater influence on fire activity than fine fuels and biomass. Other researchers found that the surface disturbances associated with mechanical treatments may facilitate cheatgrass expansion and lead to increased fires. At present, there is little research supporting the contention that removing pinyon and juniper reduces fire.”

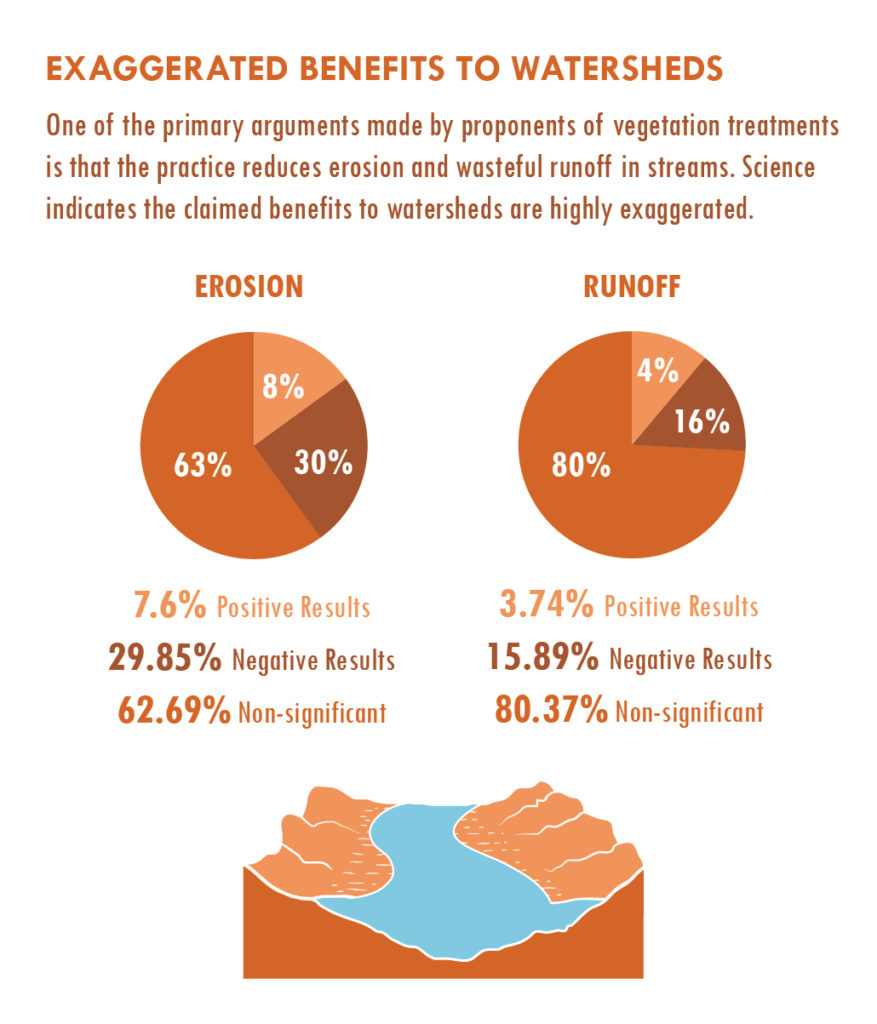

Better Ways to Restore Watershed Health

Watershed restoration is often touted as a secondary benefit to vegetation removal. While the report notes that myriad individual factors of a particular project area influence a project’s benefit or detriment to ground water recharge (e.g., elevation; vegetation type; and timing, amount, and type of precipitation), existing scientific reviews “have concluded that treatments do not reliably increase water yield on a watershed scale, although water availability may increase in local areas.”

Mechanical treatments disturb soils, which often leads to an increase in erosion, especially in places that rely on biological soil crusts as a component of soil stability.

Of the studies reviewed in the report, only 4% to 7% showed treatments decrease runoff and erosion. The report concludes that hand thinning of vegetation is the least disruptive method of treatment to soils.

A Gamble in Need of Reform

Scientific Recommendations and Conclusions

The Wild Utah Project report makes the following findings and recommendations:

- The use of passive restoration techniques, such as closing areas to livestock grazing and aerial or hand seeding of native species, “has not received enough attention in the [scientific] literature.”

- Passive restoration techniques – the cheapest, most cost-effective, and least disturbing to the target ecosystem – are often rarely considered by land managers in project proposals.

- Large-scale mechanical vegetation projects risk spreading fire-prone invasive species, which “may be a primary threat to persistence of ecosystems. The alarming possibility that treatments may facilitate continued expansion of these populations and degrade native communities calls for further scrutiny.”

- Vegetation removal projects are not “one size fits all.” “Planners must beware of applying the same mechanical treatments over vast areas of pinyon-juniper woodlands or agebrush steppe vegetation communities with variable site characteristics. A careful treatment plan must be designed before implementation.”

- Landscape-level projects without extensive prior study and research, as are typically proposed by land managers throughout the West, are not scientifically sound. “Practitioners should conduct small-scale, pilot field tests with the proposed treatment method before applying it on a larger scale.”

- “Pilot studies should be followed by independent post- treatment scientific validation, ideally with long-term monitoring of the site, to ensure that the proposed treatment method actually does lead to the intended ecological conditions.”

- Land managers need to define what constitutes “success” for a mechanical vegetation removal project. “As changing climatic conditions make predicting the results and risks of mechanical treatments even more uncertain, public land managers should aim for more transparency in the decision process to explain the expectations for a project and the science guiding the planning effort.”

- While many factors may be at play in causing the majority of these projects to result in “no significant effect,” “if these non-significant responses truly indicate that mechanical treatments are not producing the desired results, then a re-evaluation of their efficacy or perhaps post-treatment management is necessary.”

Policy Recommendations

The Wild Utah Project report illustrates the need for policy reform of the BLM’s vegetation removal program. SUWA suggests the BLM adopt the following guidelines for vegetation removal projects:

- Implement the least intensive, lowest risk actions first, leaving all surface-disturbing activities as a last resort. Low risk/low cost actions include removing cattle from the subject landscape and aerially seeding with native species.

- Align vegetation removal goals with the soil type of the area. For example, the BLM often argues that pinyon-juniper is “encroaching” into sagebrush habitat, but if the soil type shows that it is expected to be a pinyon-juniper forest, then the project lacks a scientific basis. Similarly, if the project area contains old-growth pinyon-juniper forest, the “encroachment” theory lacks merit.

- Take a precautionary approach to project size. Large-scale vegetation removal should not occur until the BLM develops defensible procedures and methods that ensure a high-likelihood of project success.

- Develop scientifically-robust monitoring protocols and utilize untreated reference areas to ensure that there is a baseline against which results can be compared.

- Include adequate funding for long-term monitoring and development of peer-reviewed scientific literature as part of project proposals. The BLM should partner with the U.S. Geological Survey when possible to assist in long-term monitoring.

- Analyze the impact of vegetation projects on biological soil crust and non-game species dependent on pinyon-juniper forests and sagebrush stands.

- Stop vegetation removal on wilderness-quality lands, including Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs) and BLM-identified lands with wilderness characteristics (LWCs). There are millions of acres of BLM-managed public lands in the West that lack wilderness quality, where the BLM can develop and test methods and strategies for consistently achieving desired results.

- Focus on prior vegetation removal project areas that have failed or underperformed before conducting surface-disturbing activity on previously undisturbed landscapes.

- Define meaningful goals and parameters for vegetation removal projects that define success or failure. Failing to identify specific desired outcomes limits the agency’s and the public’s ability to meaningfully analyze project efficacy.

The BLM should take a careful, scientifically-sound approach to vegetation removal and monitoring, rather than continuing to allow a desire for funding to determine project location and size.

The Wild Utah Project report illustrates the need for policy reform of the BLM’s vegetation removal program. SUWA suggests the BLM adopt the following guidelines for vegetation removal projects:

- Implement the least intensive, lowest risk actions first, leaving all surface-disturbing activities as a last resort. Low risk/low cost actions include removing cattle from the subject landscape and aerially seeding with native species.

- Align vegetation removal goals with the soil type of the area. For example, the BLM often argues that pinyon-juniper is “encroaching” into sagebrush habitat, but if the soil type shows that it is expected to be a pinyon-juniper forest, then the project lacks a scientific basis. Similarly, if the project area contains old-growth pinyon-juniper forest, the “encroachment” theory lacks merit.

- Take a precautionary approach to project size. Large-scale vegetation removal should not occur until the BLM develops defensible procedures and methods that ensure a high-likelihood of project success.

- Develop scientifically-robust monitoring protocols and utilize untreated reference areas to ensure that there is a baseline against which results can be compared.

- Include adequate funding for long-term monitoring and development of peer-reviewed scientific literature as part of project proposals. The BLM should partner with the U.S. Geological Survey when possible to assist in long-term monitoring.

- Analyze the impact of vegetation projects on biological soil crust and non-game species dependent on pinyon-juniper forests and sagebrush stands.

- Stop vegetation removal on wilderness-quality lands, including Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs) and BLM-identified lands with wilderness characteristics (LWCs). There are millions of acres of BLM-managed public lands in the West that lack wilderness quality, where the BLM can develop and test methods and strategies for consistently achieving desired results.

- Focus on prior vegetation removal project areas that have failed or underperformed before conducting surface-disturbing activity on previously undisturbed landscapes.

- Define meaningful goals and parameters for vegetation removal projects that define success or failure. Failing to identify specific desired outcomes limits the agency’s and the public’s ability to meaningfully analyze project efficacy.

The BLM should take a careful, scientifically-sound approach to vegetation removal and monitoring, rather than continuing to allow a desire for funding to determine project location and size.