After three years the wait is over. In January, Rep. Rob Bishop (R-UT) finally unveiled a draft of his Public Lands Initiative (PLI). Even before its release, the tenor of discussions with congressional offices had prepared us for bad news. Sadly, the draft dwarfed our worst fears.

The Bishop bill may be the worst piece of proposed Utah public lands legislation SUWA has ever encountered. It is a fossil fuel development bill that would further the Utah Legislature’s land grab while rolling back wilderness management—all shabbily masquerading as some sort of milestone conservation measure. Conjure your worst nightmares for Utah’s canyon country and chances are Bishop has done what he can to make them reality.

Before we get to details—and they are all gory—here’s a quick recap about how we got where we are today. (For more details, see feature story in our Autumn/Winter 2015 issue.) Three years ago, Bishop announced that he would try to put together legislation for the public lands of eastern Utah. We jumped into the process in the good-faith hope that this effort would be different from its predecessors.

It certainly began that way. Staffers for Bishop and his partner in the effort, Rep. Jason Chaffetz (R-UT), met with us and listened. We soon reached a landmark agreement in Daggett County that Bishop promised would be in the PLI legislation as the first of what we hoped would be many like it. The Daggett compromise would have protected significant amounts of public land in exchange for some development opportunities for the county. The deal was widely praised—except by one disgruntled, newly-elected Daggett County commissioner. So Bishop reneged and pulled the Daggett agreement out of the PLI. It was all downhill after that.

Bishop and Chaffetz became palpably less interested in the public’s views than in the demands of rural county commissioners representing 5 percent of Utah’s population and 0.05 percent of the U.S. population. Many of these commissioners felt little need to listen. San Juan County commissioners specifically said they wouldn’t take comments from anyone living outside the county.

By the summer of 2015 the writing was on the wall: Bishop and Chaffetz planned to mostly just follow the county proposals. We knew what the counties wanted so we braced ourselves for a bad bill. When hurricane PLI hit in January, it was worse than anything we had anticipated.

A Disaster for Utah’s Public Lands

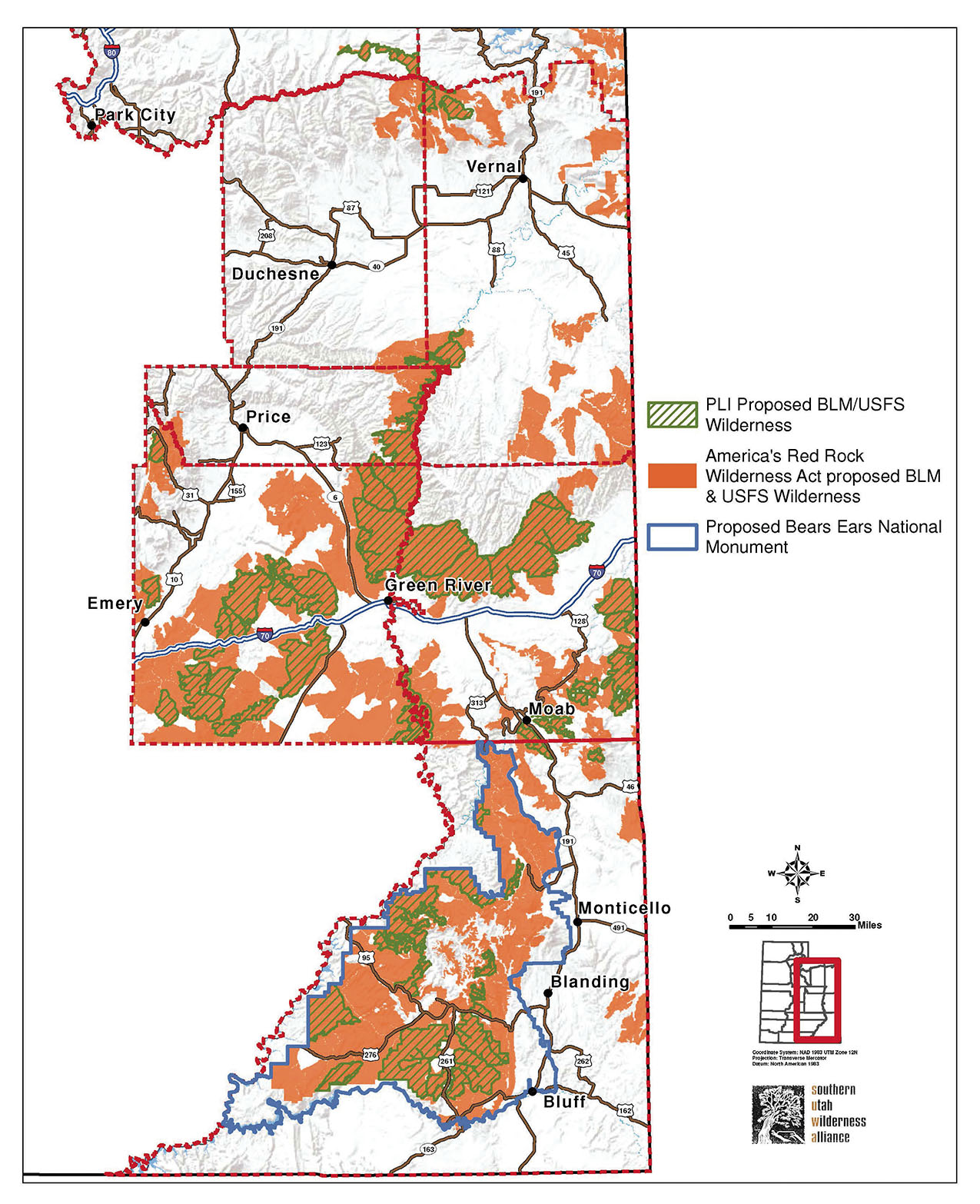

Bishop has said that he wanted to develop the PLI to provide certainty. He succeeded . . . disastrously. His bill guarantees that millions of acres will be dedicated to fossil fuels and that the Utah Legislature will receive a major boost in its land grab caper (see map in center spread).

Were it to pass, the PLI would be a boon for fossil fuel development; the corollary, of course, is that it would be bad for the planet, its climate, and for the long-term health of Utahns. Hidden in the details of the PLI is a provision to create expansive “energy planning areas” where oil, gas, tar sands, coal, and oil shale development—along with any other extractive activity you can think of—are prioritized above all else. Not one for half measures, Bishop then greases the skids so that this development happens as quickly as possible.

The PLI designates 2.5 million acres of public lands as permanent fossil fuel zones—more land than it designates as watered-down wilderness! Somehow, neither Bishop nor Chaffetz has ever disclosed this number to the public. Their PLI website omits any maps of the fossil fuel zones.

Bishop would legislate a corridor to allow the state to build its Book Cliffs highway, more aptly known as the tar sands highway—a route designed to bring intensive fossil fuel development to the southern Book Cliffs. He also provides for a disastrous land exchange, trading low-value state land for high-value federal land. The clear aim is to accelerate oil and gas development in the southern Book Cliffs and elsewhere.

Land Grabs Are Us

The PLI celebrates the Utah Legislature/Bundy/Ken Ivory land-seizure agenda. The draft legislation gives the state more than 10,000 miles of dirt roads, two-tracks, and cow trails as 66-foot-wide highway rights-of-way. It then allows the state to continue to pursue its litigation claiming the remaining 2,000 miles of routes that would be located inside wilderness and other conservation areas.

Bishop’s draft surrenders to the state management of 110,000 acres of public land surrounding Goblin Valley. The director of Utah’s state parks is particularly keen on this scheme, apparently just so he can open up to vehicular travel the long-closed Muddy Creek as it passes through the San Rafael Swell. Bishop also proposes to give tens of thousands of acres of other public lands to the state, counties, and private citizens. If the dreadful bill were passed, Utah would take over beloved places like the Six-shooter peaks just outside Canyonlands National Park.

The PLI effectively gives the state and counties management control of most of the conservation areas it proposes, thereby negating any conservation value in those designations. In these areas, federal land managers that do not adopt state or county management proposals would be required to submit a report to Congress. Here’s betting that no BLM official would ever file such a report and would buckle under local pressure. There is no similar provision for this anywhere, not even on unprotected public lands. Imagine what will happen to our public lands when county commissioners like Phil Lyman—convicted leader of an illegal off-road vehicle ride—or state legislators like Mike Noel get to call the shots.

And in one last sinister move, the PLI includes a blank space in its final provision. There, Bishop and Chaffetz intend to insert language depriving the president of his Antiquities Act authority to designate national monuments in the PLI region.

What about Conservation?

What about Conservation?

But surely, you say, there must be some grand offsetting conservation provisions to make up for such a tawdry list of giveaways. Unfortunately, no. The only unqualified, positive provision for conservation in this bill is a 19,000-acre expansion of Arches National Park. Everything else the PLI does is the cynical antithesis of the conservation it claims to be.

Take wilderness, for example: the PLI does not designate any real wilderness. Instead, Bishop and Chaffetz have substituted some cheap imitation loaded with loopholes and harmful management language. For example, they would give grazing more protection in designated wilderness than it has on lands not proposed for conservation management. They would allow Utah’s Department of Agriculture to shoot coyotes from helicopters, currently impermissible in wilderness.

Bishop’s wilderness management language is so foul that it would actually lower the standard by which Arches and Canyonlands national parks are managed, and this is where a sizable chunk of the PLI’s designated wilderness would be located. In these parks the PLI would actually decrease airshed protections intended to keep the air clean.

Rather than seeking to protect deserving landscapes in Utah, Rep. Bishop is trying to use this bill to dilute the very idea of wilderness in the United States. He has been clear that his goal as Chair of the U.S. House Committee on Natural Resources is to do just that.

Even if the PLI included standard, authentic wilderness management language, it would result in wilderness management for less public land in Utah than is the case today. The Bureau of Land Management has more de facto wilderness in the form of wilderness study areas and natural areas than the PLI would designate. So under the PLI not only do we get millions of acres dedicated to fossil fuels and to advancing the Utah land grab, we end up with less land managed as wilderness. Some deal.

The PLI also includes euphemistically-termed “conservation areas” and “special management areas.” These designations do little to promote preservation. For example, one special management area is to be run so that it “promotes an economically sustainable commercial forest products industry.” Huh? Since when did designating an area for logging count as conservation?

The so-called conservation areas are littered with roads and all sorts of anti-preservation provisions. The PLI permits large-scale pinyon and juniper removal through mastication machines in conservation areas. It also enshrines grazing here as it does in its quasi-wilderness areas. Remember, these conservation areas would be managed for the most part by the demands of the state and its counties. Pity the poor land manager forced to explain to Congress why he departed from locals’ wishes.

But There Is Hope

The PLI is not a good-faith proposal. It feels a little bit like Bishop went to a Tesla showroom and made an opening offer of $10. That is no starting point for a negotiation; it is an invitation to be laughed out of the room. The PLI does a great disservice to the amazing public lands of eastern Utah and should be scrapped altogether. It is a sad waste of goodwill and three years worth of extensive talks.

So we have begun an aggressive campaign to fight this Trojan horse and SUWA’s members have risen to the occasion. We ran commercials on network and cable TV as well as electronic ads. SUWA members have been barraging Bishop’s office with letters protesting the PLI. We joined our conservation partners to host a public hearing in Salt Lake City where hundreds came to register their disappointment with the PLI. With your help, we will continue to fight this bill and stop it from passing Congress.

Bishop’s PLI has imploded. This, however, clears the way for President Barack Obama to use his Antiquities Act authority to designate the Bears Ears National Monument. Both Bishop and Chaffetz have known for some time that an illegitimate proposal like their draft PLI would be an invitation for just such an outcome. Rather than turn these lands into fossil fuel zones or 66-foot-wide highways, as the PLI would do, let us ask that President Obama protect them for present and future generations. That is real conservation.

—David Garbett

(From Redrock Wilderness newsletter, Spring 2016 issue)