Today, October 15th is National Fossil Day! We celebrate it with the acknowledgement that as a repository of scientific discovery, Greater Canyonlands holds a treasure trove of found and yet-to-be-found paleontological secrets.

The geologic formations that dominate southeastern Utah are known for harboring numerous dinosaur tracks and bones, ancient fossilized plants and marine invertebrate. But a lack of resources means that much work remains to find even more. Missing puzzle pieces that could be found in Greater Canyonlands may provide answers to outstanding scientific questions, such as:

• How did ancient sea life evolve to life on land?

• What did those first land-dwellers look like?

• Did it happen in southern Utah?

• For dinosaurs, what sizes, shapes and types left traces behind?

Paleontological potential exists in Greater Canyonlands in two main time periods (although many periods are present): the late Jurassic, around 140-160 million years ago, and the Permian, around 250-300 million years ago.

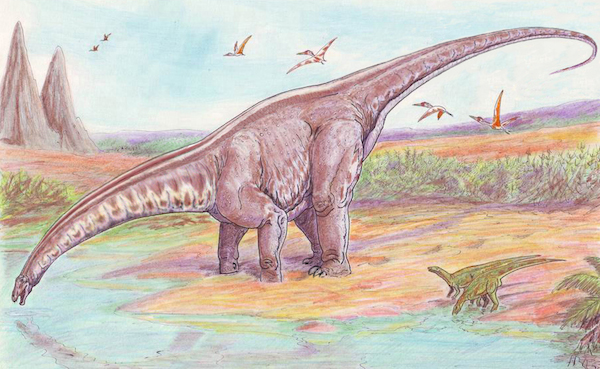

The Jurassic is known for meat-eating dinosaurs such as Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus, and large plant-eaters such as Apatosaurus and Diplodocus. Permian creatures of the late Paleozoic era are before the age of dinosaurs, and include Tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) that hold keys to understanding how life emerged from the seas to land. The fossilized remains from both periods are largely still in the ground in Greater Canyonlands, awaiting discovery and research.

Dinosaur tracks are also found in Greater Canyonlands, and the area around Moab has the highest density of known tracks in North America. We know this through casual observation and discovery by curious hikers and off-road vehicle enthusiasts who happen to stumble across ancient footprint impressions in the sandstone as they venture in the backcountry. While these amateur finds are sometimes reported, many times they are not.

Interpreting important remains, luckily found through non-scientific discovery, is no way to conduct systematic research, but a dedicated program that emphasizes science, and one that attracts full-time paleontologists is a breakthrough waiting to happen.

When we attain knowledge of how earth’s creatures from millions of years ago acted, walked, reproduced, ate and lived, we can learn know more about ourselves and the world we currently inhabit.

Greater Canyonlands is an educational opportunity we have yet to take advantage of. Digging fossils is the dream of children everywhere. Nobody needs reminding that kids dig dinosaurs and fossils. We’ve all been there, and our kids are currently as fascinated with the remains of these ancient earth creatures as we were.

University students are fascinated too. Jason Dillingham of Snow College in central Utah described his excitement about dinosaur digs in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument “I think it’s a big adventure for me, personally. I think it’s pretty awesome. It’s amazing.”

Even adults get into the fun, as Jeanette Bonnell, an amateur scientist and dinosaur enthusiast with Utah Friends of Paleontology, recently said “The experience of finding your first fossil is indescribable.”

After President Clinton signed the 1996 proclamation that set aside Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, funding flowed to research. This funding is what made possible the finds of Nasutoceratops titusi or Big Nose horned dinosaurs, and others, in the Grand Staircase-Escalante.

Similar scientific finds are possible in Greater Canyonlands, but we need the courage to place a higher importance on scientific research in the area, rather than let it be squandered for the short term profit of fossil fuels that would otherwise be emphasized.

A proclamation for Greater Canyonlands that supports public land agencies to focus on research and science is critical to unleashing this potential – without it, we may never know what’s out there, because there isn’t the direction or the money to look.