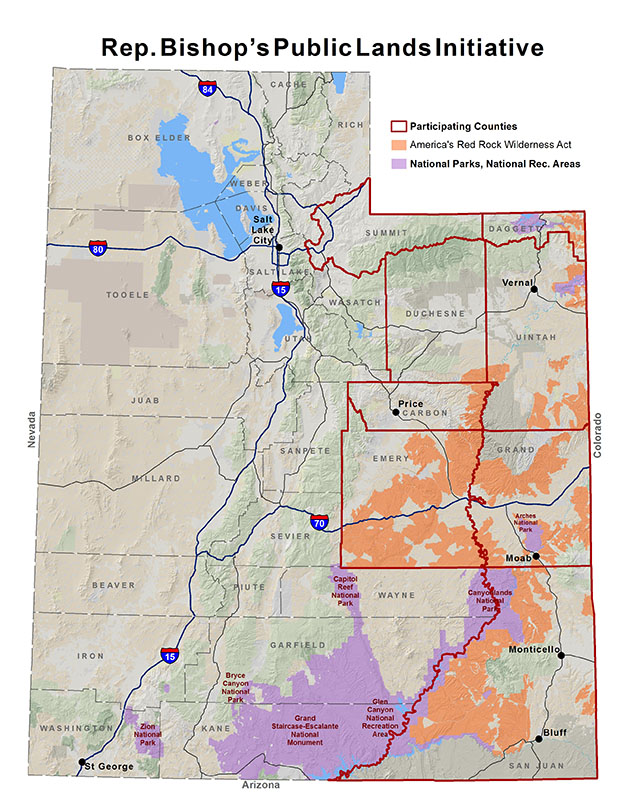

It’s been over two years since Rep. Rob Bishop (R-UT) approached various stakeholders, including us, with a big plan: to create comprehensive public lands legislation for several counties in eastern Utah—legislation that simultaneously would protect wilderness, facilitate land trades, and perhaps give counties some of goodies they’ve always wanted in exchange.

It’s been over two years since Rep. Rob Bishop (R-UT) approached various stakeholders, including us, with a big plan: to create comprehensive public lands legislation for several counties in eastern Utah—legislation that simultaneously would protect wilderness, facilitate land trades, and perhaps give counties some of goodies they’ve always wanted in exchange.

We admired that Bishop, as a member of Utah’s often wilderness-hostile delegation, dared wade into the tangled political battle that has raged over the future of Utah’s wild lands. At SUWA we’ve spent three decades holding the line for the land, protecting it from the greedy and the woefully unimaginative. We’ve done so in the hope that eventually we’d chip away a foothold to climb toward permanent protection. Rob Bishop offered such a foothold, and together we took a tentative step.

We’re now edging closer to the end point of what has been a very tumultuous course. While we reached a formal agreement in two counties, Daggett and Summit, similar discussions have not taken place in many of the others, and Daggett is even signaling it may renege. The original deadline for a complete draft, March 27th, came and went without one. Now we think a draft may be out by early summer, or perhaps before you read this newsletter.

We can’t be sure whether the Public Lands Initiative (PLI), as it’s called, will be something we support, something we have to fix, or something we’re forced to fight. It all depends on the delegation—will they swallow county proposals whole and put them in the bill, or will they force the counties to compromise, as so many have refused?

The stakes are stupendously high. About 5.5 million acres of wilderness-quality land hang in the balance. The places we must protect in order to call the PLI a success are the most inspiring, rugged and worthy lands still eligible for wilderness protection in the U.S. And we’re not going to support a bill that doesn’t do justice to them, or is a step back for conservation.

Here are just a few of the places we are still fighting for in the discussions. A lot of crucial work remains.

Desolation Canyon

John Wesley Powell must have been acutely aware of the region’s sublime loneliness when he named this 120-mile stretch of the Green River, which starts well above the Sand Wash boat ramp. At half a million acres, Desolation Canyon is the largest wilderness in the lower 48 not yet designated as such. Rafters who float its deep chasm know it holds amazing wildlife and challenging adventure in equal measure. But Desolation crosses five counties, imperiling its upper reaches due to political vagaries irrelevant on the land. A draft propsal by county commissioners would roll back existing protections for wilderness study areas and leave Desolation vulnerable to oil and gas development.

Mussentuchit Badlands Complex

A kaleidoscope of colorful layers, the “Musn’t Touch It” Badlands and surrounding landscape are a rugged and eerie series of highly erosive features, and as such have been named by the BLM as a critical soil and watershed area. These lands, which hug the west side of the San Rafael Swell, are essential to completing meaningful protections there. They bring a much-needed diversity to the kinds of places preserved in designated wilderness and are a surreal wonderland for hikers and recreationists. Emery County’s proposal ignores these values, favoring instead the ephemeral dreams of small-time oil and gas prospectors.

Hatch and Harts Draw Complex

Hatch and Harts Points, two important features of this complex, stand sentinel high above visitors entering Canyonlands National Park. This plateau and canyon system would seem to most people to be a part of the park, but it is completely unprotected BLM land that is increasingly targeted by developers. Campers can bunk down for the night in the BLM’s nearby Windwhistle Campground and from there embark on great day hikes into Bobby’s Hole Canyon and the Hart’s rim, making it a perfect venue for a whole-family wilderness outing. Sadly, San Juan County would sacrifice this vast landscape for energy and potash development.

Bitter Creek Complex

A veritable ark of creatures roam Uintah County’s border with Colorado in the Bitter Creek complex of the upper Book Cliffs. This refuge for bear, cougar, elk, and deer has surely earned its nickname of “Utah’s Serengeti.” It’s as important for these species as it is to the humans who visit to hunt, fish, camp and recreate there. But Uintah County is so far demanding regressive protections, even proposing dropping Wilderness Study Areas for extractive development. We cannot support a bill that is only a step backward for Uintah, and protecting Bitter Creek will be essential to ensuring it’s not.

White Canyon Complex

The web of canyons whittled into the sandstone of White Canyon created a canyoneer’s fantasy, where whimsical slots and wide gulfs alternately stretch between the east edge of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and the northwest border of Natural Bridges National Monument. Like so many places in Utah, the expanse connecting those two federally acknowledged sites was left unprotected, leaving its critical Bighorn sheep rutting and lambing habitat, the cornucopia of archeological sites, and the thrill that comes with getting lost on purpose all vulnerable to development.

Labyrinth Canyon

The Green River loops and twists like a drunken bumblebee through Labyrinth Canyon on its way to Canyonlands National Park. This is one of the few places in the western United States where families can enjoy a week-long, flatwater wilderness-quality canoe trip. In the bosom of Laby, the river reveals hikes to incredible side canyons, and to cultural sites so intact we might wonder if paddling faster could catch us up to their ancient architects. It’s a world-class river trip, and an irreplaceable one now that our thirst for progress has altered most of our nation’s precious waterways. Failing to protect Labyrinth as wilderness is failing. Period.

These places are just a few of the many for which we are advocating in the PLI. But even as we momentarily lay down our swords for the olive branches we’ve extended to the Utah delegation, know this: the PLI is only the next chapter. If we can protect significant wilderness permanently, even with the help of former foes, we are certainly not too proud to do so.

We have invested thousands of hours trying to do just that. SUWA staff have traveled to far-flung corners, meeting with county commissioners, stakeholders, and congressional staff seeking acceptable compromise. Our members have written letters, attended meetings, and proselytized for wilderness. We sincerely hope this bill results in meaningful protection for Utah’s spectacular wild lands.

But if we’re presented with a cluster of proposals dreamed up by the counties without meaningful conservation gains? We’ve killed bills like that 15 times. We haven’t forgotten our mission, and we haven’t forgotten where we keep our swords. We also haven’t forgotten that you make it all possible, and no matter what the outcome, we’ll need your help.

—Jen Ujifusa

(from Redrock Wilderness newsletter, Spring 2015 issue)